It can be difficult to understand the different forms of property ownership in France. We have written this article to give you a clear and accessible understanding by applying them to the ownership of a rural property, whether agricultural, equestrian, vineyard, forestry or residential.

It is crucial to understand the different options available to you when it comes to owning property. This will enable you to make informed decisions, protect your interests and optimise the use of your property. Whether you are interested in full ownership, joint ownership, usufruct, life annuity or other forms of property ownership, we will explore each of them.

Full ownership is the most common and well-known form of property ownership and is applied by default. It represents total and exclusive ownership of a property. In other words, being a full owner means having all the rights to a property, including the right to use, modify, rent, sell or destroy it, subject to the laws and regulations in force.

As a "full owner", you have various rights and responsibilities. Firstly, you have the power to enjoy your property to the full. This means that you can occupy it, live in it or use it according to your needs and wishes. You also have the option of temporarily letting your property, which can generate income.

However, full ownership also comes with responsibilities. You are responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of your property, as well as the associated charges and taxes. This includes repair costs, property tax, insurance and ongoing property expenses.

Freehold ownership offers a number of advantages to rural landowners. Firstly, it gives you a great deal of freedom in how you use your property. You can exploit your property according to your own needs and aspirations, whether for farming, viticulture, livestock farming, landscaping or other rural activities. You have complete control over decisions concerning your property, without having to consult other parties.

What's more, full ownership offers long-term stability and security. There are no time limits, and you can pass your property on to your heirs or sell it as you wish. Full ownership therefore represents a lasting legacy for future generations.

On the downside, acquiring a freehold rural property can require a substantial financial investment. What's more, you are solely responsible for the costs of maintaining and managing the property. In a rural context, this can involve considerable expenditure on land maintenance, farm buildings, etc.

Dismemberment of ownership involves the separation of ownership rights between two distinct parties: the bare owner and the usufructuary. This division creates a coexistence of rights over the same property, with specific roles and rights for each party.

The bare owner holds bare ownership, i.e. the rights of ownership over the property, with the exception of its use and income. The main role of the bare owner is to own the property as a future owner, once the usufruct has ended. However, for the duration of the usufruct, the bare owner does not have the right to use the property or to receive any income it may generate.

The rights of the bare owner include the right to dispose of the bare property, for example by selling it or passing it on by inheritance. However, these rights are limited by the rights of the beneficial owner during the period of dismemberment. The bare owner also has a duty to maintain the property and keep it in good condition until the end of the dismemberment period.

On the other hand, the usufructuary holds the usufruct, which gives him the right to use the property and receive its income for the duration of the dismemberment. The usufructuary can live in the property, rent it out and collect the rent, or use the income from the property. In return, the usufructuary must pay maintenance costs, property tax, etc.

Les droits de l'usufruitier sont temporaires et sont limités par la durée du démembrement ou par son décès. L'usufruitier a le droit de jouir du bien et d'en percevoir les fruits, mais il ne peut pas disposer de la nue-propriété sans le consentement du nu-propriétaire .

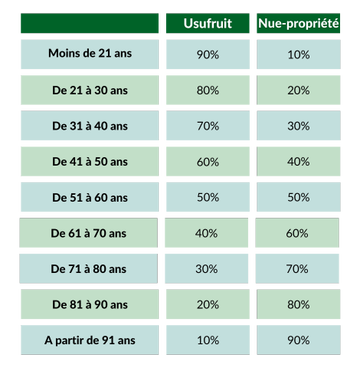

Usufruct is generally a life interest, i.e. it disappears on the death of the usufructuary and joins bare ownership, thereby reconstituting full ownership of the property. In this case, the value of the usufruct (and therefore of the bare ownership) from a tax point of view is determined by the age of the usufructuary:

The usufruct can be successive, meaning that it will pass successively to several beneficiaries, usually in a predetermined order. For example, an owner may make a gift with a reservation of usufruct and arrange for the usufruct to pass to his or her spouse on his or her death, and then to his or her children after the spouse's death. This form of ownership allows the use and income from the property to be passed on gradually to different generations, while retaining the property itself.

Usufruct can also be temporary. In this case, it is valued for tax purposes at 23% of the value of the full ownership for each 10-year period.

The dismemberment of ownership can be advantageous in a number of situations.

Firstly, it can enable an owner to pass on his or her assets while retaining certain rights, in particular the right to continue using the property during his or her lifetime. This can be particularly interesting for rural owners who wish to gradually relieve themselves of the management of their property while retaining the benefits.

In addition, ownership stripping can be used as an estate and tax planning strategy. For example, an owner can pass on bare ownership of their property to their descendants. The gift tax will be calculated on a lower value than the value of the full ownership (valuation of the usufruct according to the age of the usufructuary), which will reduce the amount of tax payable. On the death of the usufructuary, the usufruct automatically joins the bare ownership with no additional duties to pay.

In practice, the owner makes a gift of the bare ownership to his or her heirs. The gift tax is calculated on a reduced value (depending on the age of the usufructuary) and will therefore be lower than that which would be calculated on the full ownership of the property.

When the usufructuary dies, the usufruct automatically joins the bare ownership to reconstitute the full ownership. This transaction is not subject to inheritance tax.

However, it is essential to understand the tax and inheritance consequences of ownership dismemberment. For example, it is the usufructuary who will be liable for property tax and also for Impôt sur la Fortune Immobilière (property wealth tax) on the value of the property in full ownership.

The dismemberment of ownership often finds a practical use in the context of the transfer of rural properties and, more broadly, businesses.

A farmer reaching retirement age, for example, can make a gift of farmland to his children with a reservation of usufruct. The land is then leased to the new owner, whether or not he is the heir. In this way, the young retiree can pass on his land to his descendants at a lower cost. At the same time, they have safeguarded additional income for themselves when they retire through the collection of farm rents.

A life annuity is a special type of property sale where the property is paid for in the form of a life annuity, i.e. a periodic payment until the death of the vendor. This form of transaction offers an interesting alternative for rural owners wishing to sell their property while ensuring a regular income for the rest of their lives.

There are two parties involved in a life annuity: the seller, also known as the creditor, and the buyer, known as the debtor. The role of the creditor is to sell the property and receive the life annuity for the rest of his or her life. The amount of the annuity is generally set at the time of sale, taking into account factors such as the age of the annuitant, the value of the property and the specific terms of the transaction.

On the other hand, the debtor, as purchaser, undertakes to pay the life annuity to the creditor. In addition to the annuity, the debtor also assumes the charges and responsibilities associated with the property, including maintenance costs and property taxes. The debtor acquires full ownership of the property, but will not be able to enjoy it fully until after the death of the creditor.

A life annuity sale allows the costs and constraints associated with managing and maintaining the property to be passed on, while retaining the use of the property. This can be attractive to rural landowners who wish to offload the responsibilities associated with ownership while benefiting from an ongoing income.

However, it is important to consider some of the disadvantages of life annuities. For example, the amount of the life annuity can be influenced by a number of factors, such as the life expectancy of the annuitant, economic conditions and the characteristics of the property.

Life annuities also present risks for the purchaser, including the risk of paying an annuity over a long period if the annuitant lives longer than expected. In addition, the buyer must take into account the costs and responsibilities associated with the property for the duration of the life annuity.

Companies are increasingly being used to own property, particularly through property companies. However, all types of company, whether civil or commercial, can own property, particularly rural property.

Setting up a company will add complexity to the process of owning and managing a property (incorporation, accounting, general meetings, etc.), but it does meet certain objectives:

It is also possible to dismember ownership of either the shares held by the partners or the buildings owned by the company.

It is essential to seek specialist advice before embarking on the incorporation of a company, which will take account of your personal situation and objectives to advise you on the appropriate legal course to take.

Companies are being used more and more in rural areas, whether for specific property companies: Groupement Foncier Agricole, Groupement Foncier Viticole, Groupement Forestiers, etc., or for farming companies: sociétés civiles, EARL, GAEC, etc. They make it possible to organise the ownership and transfer of rural assets, to organise work between several people, to choose different social regimes, etc.

The use of long-term leases associated with Groupements Fonciers means you can benefit from additional exemptions from inheritance tax.

In addition to the forms of property ownership already mentioned, there are other less common but equally important concepts to be aware of. One of these is emphyteusis, which can have interesting applications in the rural context.

Emphyteusis (or emphyteutic lease) is a form of property ownership in which an owner grants a real right to another person, called the emphyteutic lessee, to use and exploit the property for an extended period, usually several decades. The emphyteutic lessee has the right to enjoy the property and to receive the fruits thereof, while having the obligation to maintain and conserve the property. At the end of the long lease, the property automatically reverts to the original owner.

Emphyteusis can be used for long-term projects in rural areas, such as leasing agricultural land over an extended period. It offers farmers and operators the stability and security they need to develop and invest in their businesses, while preserving long-term ownership of the land.

We hope you will find this article useful in gaining a clear understanding of the different forms of property ownership in France, focusing on those most relevant to rural landowners without prior legal knowledge.

Each form of ownership has its own characteristics, rights and responsibilities for owners. It is essential to understand the advantages and disadvantages of each form in order to make informed decisions about the management of one's rural property assets.

It is important to remember that each situation is unique, and it is advisable to consult a professional specialising in property law or estate planning for personalised advice. These experts can help assess the rural owner's specific objectives, needs and constraints, and provide solutions tailored to his or her situation.